If there is a hell for game writers it is filled with ideas that never got fullfiled. Being innovative is a gift, but inappropriately used, it also becomes a curse.

It is easy to say that everything has already been done. The number of topics that culture deals with is obviously limited. Literature, books games – all of them circle around timeless themes.

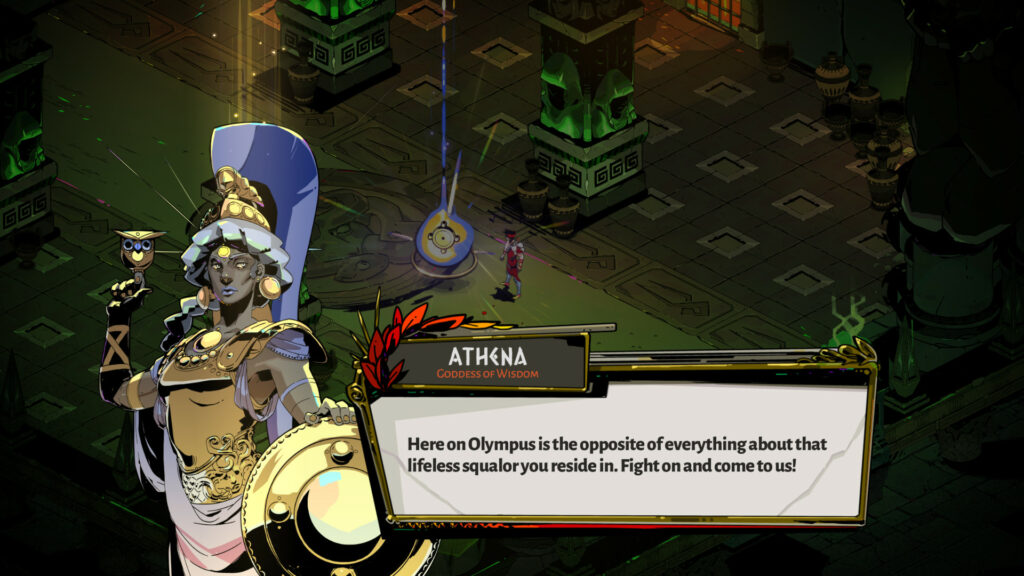

In the case of games leading theme for a good few years has been family relationships. Look at The Witcher, God Of War, Last of Us, or Hades. The dissection of family relationships takes place in many games regardless of the type of gameplay. The same theme finds many different representations.

Success, or the dark object of desire

Fame, glitz and glamour. Naturally this what many scriptwriters, secretly or not, dream about. They want their idea to inspire, and the game they work on to be a big success. Among people who aspire to be game scriptwriters, I usually observe two approaches:

– Copying ideas from other games, with some tweaking. Building on the success of another title with the hope that if audience liked one, they will like the other one too, since both are similar.

– Creating your own often very elaborate world where it is hard to pin down the theme, to find the dominant plot path, or even to define the main characters.

Repeating of ideas

The first trend reminds me of the copy-paste phenomena occurring in mobile games. For one successful title there are several other games sometimes with similar names and mechanics. In the case of game storylines such “copying” is not only on the verge of plagiarism, but also results in a flood of generic storylines based on genre clichés.

However, not all clichés are a bad thing. Chris Klug and Josiah Lebowitz, in their book “Interactive Storytelling for Video Games: A Player-centered Approach to Creating Memorable Characters and Stories,” distinguish several conditions that define the wise use of clichés:

A) deliberate use of repetitive patterns.

B) controlling the number of clichés.

C) Bringing something new even to worn-out plot clichés, modifying archetypes and audience habits. Why should a mafioso always smoke a cigar? Why does the prince always have to save the princess? Why is it the Chosen One who always saves the world?

(D) the use of clichés to confuse the player and lull his alertness.

I would add one more point to Klug and Lebowitz’s rich study:

E) stay up-to-date. What was a revolution yesterday may become out-dated today and be considered a cliché.

(Too) joyful creativity

Creating worlds is extremely fun, but it is also very expensive. From a realistic point of view very few young game writers will be entrusted with enough ressources to pursue their vision. They will much more likely get a project with an already established framework and budget. At that point out of the box thinking suddenly becomes a burden. What was supposed to be a beautiful adventure in the open world of game dev throws the writer in a labirynth of narrow corridors full of monotonusly ticking clocks.

Toward the golden ratio

It is a platitude that good scriptwriter has to balance between his own creativity and the demands of the industry. Scriptwriting textbooks are full of similiar advice, but they too general to be helpful. In my next post I will address this problem using a case studies from the games I worked on.